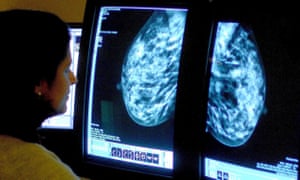

Women who rely on the most commonly used form of hormone replacement therapy are roughly three times more likely to develop breast cancer than those who do not use it, according to a study whose results suggest the risk of illness has been previously understated.

Those using the combined HRT therapy, a combination of oestrogen and progestogen, were running a risk 2.7 times greater than non-users, according to a study by scientists at the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London.

Previous investigations may have underestimated the increased risk by up to 60%, the study added.

Anthony Swerdlow, professor of epidemiology at the ICR, said: “What we found is that the risks with combined HRT are larger than most of the literature would suggest.”

The study’s leaders added that HRT is an individual choice but one for which accurate information is essential.

An estimated one in 10 women in their 50s use HRT to deal with menopausal symptoms including hot flushes, night sweats, insomnia, mood swings and tiredness.

The treatment is effective but controversial because studies published in 2002 and 2003 have previously suggested there is also link with breast cancer. Those findings led to a halving of the numbers of women taking the drugs.

In November an NHS watchdog, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), sought to reassure women about the safety of the treatment,which replaces depleted oestrogen and – in combined HRT – progestogen to alleviate symptoms.

Most women take combined HRT because oestrogen alone can increase the risk of womb cancer and taking progestogen alongside oestrogen is known to help minimise this risk. HRT using oestrogen alone is usually recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy.

Breast Cancer Now’s chief executive, Lady Delyth Morgan, said:

“Menopause symptoms can be hellish. The really important thing about the generations study is that it’s actually a fine-tuned study that’s looking very specifically and carefully at the issue.

“It’s potentially the most accurate assessment that can be made because it’s looking at the menopausal status of the participants and it’s looking at the length of time HRT was taken and on that basis assesses the change in the risk.”

There were almost 900,000 prescriptions for combined HRT with progestogen last year, according to the NHS. The risk of breast cancer increased with duration of use, with women who had used combined HRT for more than 15 years being 3.3 times more likely to develop breast cancer than non-users.

However in women using the other type of HRT – a variant that uses oestrogen only – the scientists found that there was no overall increase in breast cancer risk compared with women who had never used HRT.

Scientists have debated the increased risk of breast cancer from HRT, which could be explained by an increased exposure to hormones affecting the development and growth of some tumours.

For the study, published in the British Journal of Cancer on Tuesday, 39,000 women were monitored for six years. During that time 775 – or nearly 2% – developed breast cancer and women using combined HRT (for an average, median duration of 5.4 years) were 2.7 times more likely to contract the disease during the treatment period than women who had never used HRT.

However, no increase in risk was seen in women using oestrogen-only HRT and a year or two after women stopped taking combined HRT, there was not a significantly increased risk of breast cancer, confirming findings of previous studies.

The experts believe the lack of follow-up information on the use of HRT and menopausal status affected the accuracy of other studies. For example failure to account for women who had stopped using HRT during the research period could lead to the risk being underestimated.

When the researchers analysed their own data without adjusting for changes in HRT use or women’s known menopause age, it led to a lower estimate of a 1.7-fold increase in risk.

Dr Heather Currie, a spokesman for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and chair of the British Menopause Society, said: “Women need clear, evidence-based information to break through the conflicts of opinion and confusion about the menopause.

“For many women, any change in breast-cancer risk is outweighed by the benefit on their quality of life, bearing in mind that there are many other factors that increase the risk of breast cancer, for example lifestyle factors.”

The Medicine and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, which monitors the safety of medicines, said it would evaluate the study and provide updated information to prescribers and users of HRT if necessary.

“Medicine safety and effectiveness is of paramount importance and under constant review,” an MHRA spokesperson said. “Our priority is to ensure that the benefits of medication outweigh the risks. Current product information on all forms of HRT carries strong warnings on breast cancer, including that the risk increases with duration of use.

“The decision to start, continue or stop HRT should be made jointly by a woman and her doctor, based on the best advice available and her own personal circumstances, including her age, her need for treatment and her medical risk factors.”

HRT treatment should be re-assessed on a yearly basis at least, the agency said.

Meanwhile a separate study has found that women who expect the worst from a type of breast cancer treatment are more likely to suffer adverse side-effects.

The research, published in the Annals of Oncology, found that women with a negative perception of receiving hormone therapies such as tamoxifen suffered nearly twice the number of side-effects than women with positive expectations or who thought the effects would not be too bad.

The authors looked at 111 women in Germany who had had treatment for hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer.

They questioned the patients about their expectations of the effect of taking hormone therapy at the start of the trial and then assessed them at three months and at two years. Those with higher expectations of side-effects at the start of the study saw a 1.8 increase in their occurrence after two years.

Prof Yvonne Nestoriuc, from the University Medical Centre, Hamburg – who led the study – said: “Our results show that expectations constitute a clinically relevant factor that influences the long-term outcome of hormone therapy.

“Expectations can be modified so as to decrease the burden of long-term side-effects and optimise adherence to preventive anti-cancer treatments in breast cancer survivors.”

- The headline of this article was amended on 23 August 2016 as it incorrectly stated that combined HRT increases the risk of breast cancer by 300%. The actual figure, according to the study’s findings, is 170%.

[Source: The Gurdian]