Warnings about the impact of tech on existing patterns of employment is an upgrade of an old story. Has the digital revolution been overstated?

“One million jobs to vanish in 10 years,” shout the Monday morning headlinesjust to get the week off to a good start. But it’s not another scary intervention in the referendum debate by a pro-European or a Brexiter. It’s more serious than that.

The culprit on this occasion is the British Retail Consortium (BRC), the people who speak for shops of many sizes and employ one in six of British workers, about 3 million people. They think that 900,000 of them (not quite the million of the FT’s headline) will disappear in the next decade, more in smaller businesses and poorer areas.

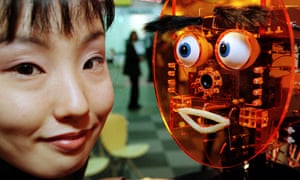

Why so? This is an upgrade of an old story, the impact of disruptive technologies on existing patterns of employment, bigger and smarter computers, more online sales. But since George Osborne decided to become the worker’s friend and raise the minimum wage to a “national living” variety (NLW), albeit slowly, it’s also a political story. Higher wages imposed by government will put low-paid shop workers’ jobs in danger, says the BRC.

Don’t be smug, Mr Lawyer, Ms Doctor, Sir Financial Adviser. Tech is starting to eat good middle-class jobs, much as automated production lines ate so many well-paid working-class jobs a generation ago. We know about this in journalism because our business was one of the first white-collar industries in the queue. Facebook and Google are busy eating our lunch; if we aren’t nimble enough, we’ll be pudding.

Nothing too new there either. It was Keynes who first spoke of “technological unemployment”. But it’s getting faster, as it did for handloom weavers around 1800. The result for all such businesses, so the conventional scenario goes, is the pear-shaped labour market, which sees huge rewards for a tiny elite at the top and a lot (though not enough) insecure ones for millennials working in the gig economy.

The BRC warning (it comes a month before the minimum wage rises to £7.20 for the over-25s, a £9ph NLW by 2020) couples this development – which it supports, in theory – with rising business rates, price deflation (bad for profits, good for customers) and the online shopping effect, to say it’s going to get worse for jobs. The chancellor hasn’t quite realised what he’s done, though there’s an important clue in the fact that he has done something. More on that later.

In the tech jungle, nimble firms will move fast to adapt and survive. Retail banking, as useless at tech as the NHS, is finally moving at your semi-automated local branch. So, more ponderously, is the NHS. Amazon and Morrisons have announced a hook-up, and didn’t Sainsburys eat Argos the other day? The Mirror Group is launching New Day, a mid-market newspaper to challenge the Daily Mail and the Express. Good luck all.

Gloom, gloom, gloom. But is it all true? Martin Ford’s 2015 book, The Rise of the Robots – and Jerry Kaplan’s Humans Need Not Apply – was a techno-pessimist’s vision, one in which a jobless future looms for millions (probably).

It assumes that rapid technological change will continue at the pace it has sustained since the late 18th century in Britain, a little later in most of Europe and the US, in Asia in the 20th century. Living standards barely rose for 1,000 years after the fall of the western Roman empire, along with a life of drudgery for most people. Steam power and the internal combustion engine, trains, electricity, proper medicine, good food and flush toilets, cars and aircraft, the list from thefirst industrial revolution amounted to a staggering transformation, even before we touch on the current, third and digital one. The transformation is both wonderful and scary.

But is it overstated? Is the Apple and Facebook world as transformative as the flush loo, the plane, the lightbulb and washing machine? Are fast-slowing productivity rates in most industrial countries a sign that the age of peak growth – the “30 glorious years” of postwar France – is over for us, soon for China too, as Taiwanese mega-manufacturer of iPads etc, Foxconn, shifts output towards cheaper India?

In other words, after an aberrant few decades, do we face a return to the historic norm in a medieval sense, stagnation and no steady rise in incomes for most people, great wealth for a few? That’s what French economist, Thomas Pikketty warned against in Capital, last year’s improbable bestseller.

That was reflected in Tyler Cowan’s thesis in The Great Stagnation (2011). It is shared by Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth (2016) – here’s fellow economist Paul Krugman’s review (paywall), which asks if Gordon is right and replies with “a definite maybe”.

Against which we should set optimists such as Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s The Second Machine Age (2014), which sees new technology as opening up more time for leisure, less time for drudgery in a world of ever greater abundance. It’s reviewed in a very thoughtful way by the novelist John Lanchester, along with Average is Over, by Tyler Cowen, another protagonist in the war into which the British Retail Consortium’s report stumbles.

Robert Gordon and Cowen seem to belong to a third group – I am indebted to the FT’s US commentator, Edward Luce, for an excellent overview (paywall) – who say optimists and pessimists may exaggerate an uncertain future about which we, the public, and assorted experts know less than we all think. Just look how silly many – never all – past predictions of the future, gloomy and upbeat, have proved to be. In any case, as Lanchester points out, it took more than 100 years before the first working steam engine (1712) became the first serious working train, Stephenson’s Rocket of 1829.

Most of this is way above my pay grade, but I do know a little more about politics and the way its intelligent deployment can make big differences. Luce cites Concrete Economics by Stephen Cohen and Brad Delong (2016), which uses the career of the financier and US founding father Alexander Hamilton to show how active government policy can make the difference between great success and failure. It’s what the history of the US would show if Americans had not become so resistant to the notion in recent decades. Reaganite policies have led to the financialisation of the economy and a withdrawal of the state whose strategic interventions in roads, universities, high tech, land tenure (Abraham Lincoln’s egalitarian 1861 legislation), tough regulation, built America.

That’s a picture we can all recognise, can’t we? Our high streets are full of banks, estate agents, pawnbrokers of one kind or another, and we all seem to be trying to charge each other for services such as parking, which were once free. Finance has got too big, governments know it and promise to “rebalance” the economy.

It isn’t easy, but it is always worth trying. So UK retailers are right to warn of challenges ahead, but Chancellor Osborne is also right to push, even slightly against, the spiral of lower wages, albeit at the risk of job losses. Society can’t be passive in the face of high finance and high tech.

So computers may beat us all at chess, but we still have the edge on human-to-human skills and much still needs to be done to tackle mental health problems in the ways we have done so many physical ailments with spectacular success. Is the future jobs path out of retail and into therapy?

[Source:- Thr Gurdian]